Rehousing Londoners – Planning’s Greatest Hits and Misses

The London Society, March 2023

‘Brutalism was seen as the answer to the post-war housing crisis, building at scale and speed and in concrete. Communities were fostered but the buildings failed. In the new London Vernacular, have we found acceptable typologies and resilient design the second time around?’

Geraldine Dening, Founder and co-director of ASH was invited to respond to this statement in a presention at the London Society called ‘Planning’s Greatest Hits and Misses‘ – Rehousing Londoners.

The presentation is below:

I will start with a brief critique of the initial statements proposed for this event:

- Brutalism was seen as the answer to the post-war housing crisis, building at scale and speed and in concrete.

- Communities were fostered but the buildings failed.

- In the new London vernacular have we found acceptable typologies and resilient design the second time round?

- Or should we focus more on retaining communities in-situ along with the sustainable retention and repair of the buildings they live in?

Firstly brutalism is an architectural style, not a set of housing policies. It certainly did proliferate during the post-war period, but it was housing policies that were the answer to the post-war housing crisis, not any particular architectural style. I suspect that the majority of housing developments built after the war were not brutalist per se but a low-key generic modernism (of which brutalism is of course a sub-category). Post-war housing in London (whether brutalist or simply modernist) was also often brick clad and in many cases formed its own kind of vernacular or regional variations. This conflation of a particular style of architecture with nearly half a century of house-building policy is in danger of concealing critical issues of housing policy and provision with secondary questions of style and aesthetics.

Secondly the buildings didn’t fail. On the contrary I would argue they were a tremendous success, housing many hundreds of thousands of Londoners: between 1945 and 1949, the London County Council (LCC) built 44,000 new council homes in London alone. Currently such post war housing estates contain some of the only remaining low cost and social housing in central London which has prevented London from becoming an enclave of wealth like cities such as Paris. The issue here is: what do we mean by failure?

Many post-war estates have certainly been poorly maintained and demonised and suffer from a significant lack of investment resulting in managed decline. In many cases they have also been badly refurbished – the failure in the case of Grenfell was not a failure of the original building, but of the contemporary refurbishment. This was – in large part – a result of the desire to improve its visual impact on the surrounding area, mitigating its apparant negative effect as a ‘blight’ on the financial uplift of the neighbourhood. The Grenfell tower fire was not an anomaly, but a demonstration of contemporary housing policy’s attitude towards existing social housing.

The third statement implies that brutalist or post-war housing provided neither acceptable typologies to learn from nor resilient design worthy of retaining; both of which are slightly underhand accusations that I strongly dispute. The statement also isolates design issues from wider social, economic and environmental contexts. If one can argue that Brutalism is a style that embodies the housing policies of the post-war then I would argue that New London Vernacular is similarly the manifestation of current housing policies. It is not simply a set of typologies and designs, but the embodiment of the financialisation and neoliberalisation of housing. Rather than a benign set of design codes it is actually driving the demolition of our council and social housing.

And the final statement, of course, is the one I am here to support – that the most socially beneficial, environmentally sustainable and economically viable solution to London’s housing needs is the retention, refurbishment and improvement of existing housing estates.

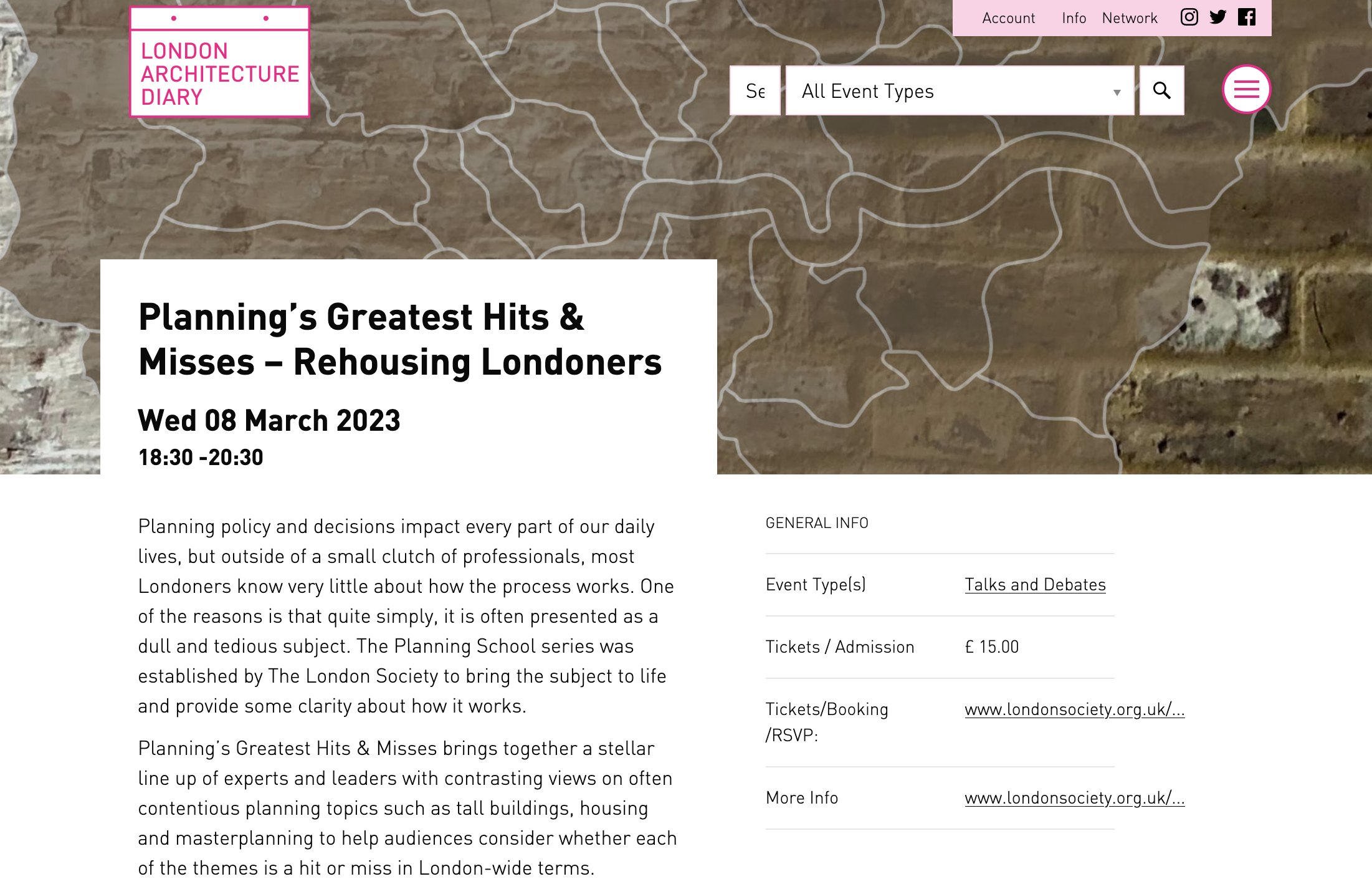

In order to define failure, we need to define what we understand as success. In public housing policy I would define ‘success’ as the housing of those that need it. The slide on the left below describes housing completions from 1946 to 2015 in a range of tenure types – pink being local authority council housing. Clearly the post war period was a tremendous success in building housing the workers of the UK needed. The diagram on the right illustrates the correlating decrease in inequality during that time, and the red line on both diagrams indicates the turning point which was the Housing act of 1980.

Under these terms, the following 40 years since 1980 are overwhelmingly a failure. 1980 saw the introduction of the Right to Buy, and the ending of the construction of social and council housing as we knew it, and the corresponding shift from housing as a use value to housing as a financial investment.

Some people might argue that the path post 1980 on the diagram on the right constitutes some kind of success – the richest 1% for example. But hopefully it is clear that this is not success for the remaining majority. Unfortunately it is along this path that housing policy has been travelling for the past 40 years and of which the London Vernacular is the latest incarnation.

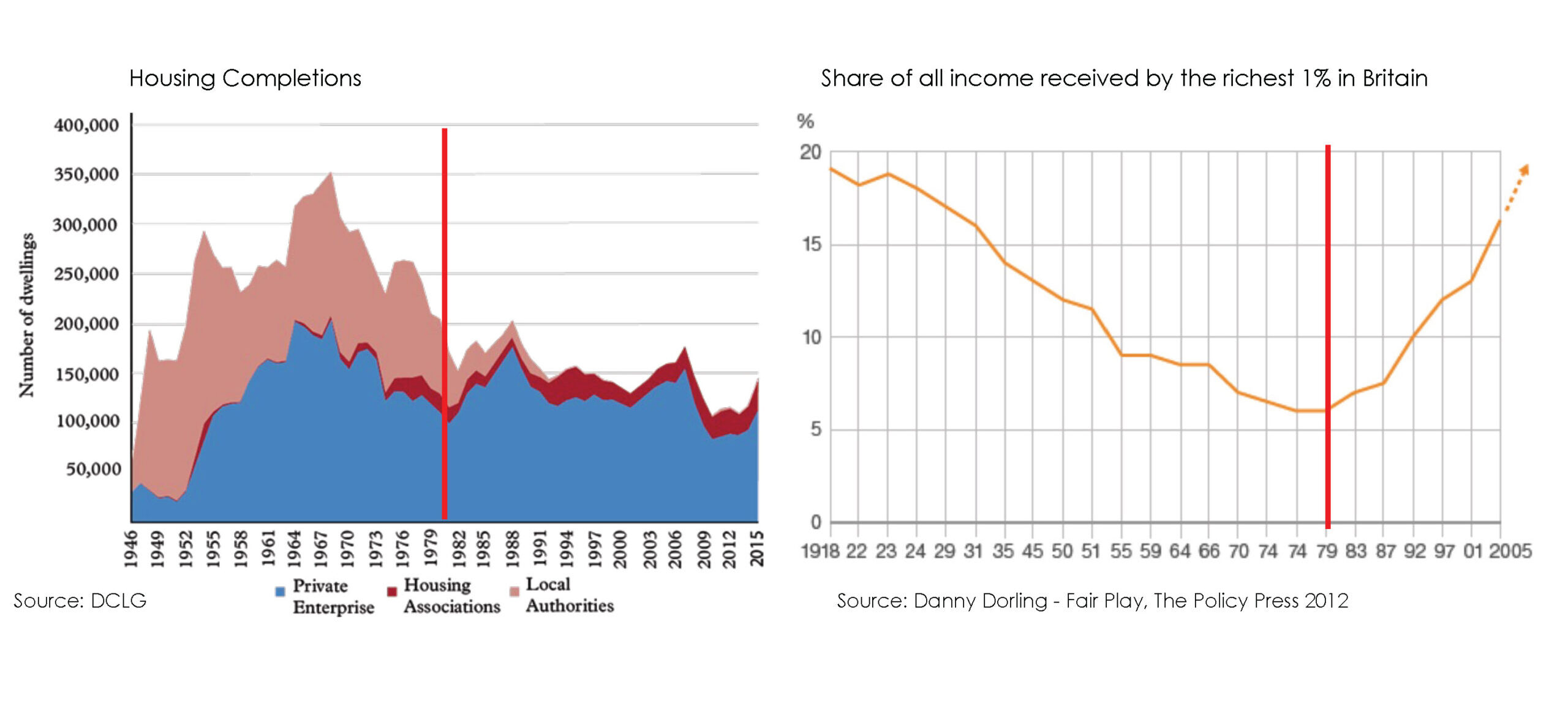

To demonstrate the consequences of current housing policies, here we can see Savills’ research showing where the demand is and where the supply. This shortfall in properties at sub-market rent and excess of provision at the top end is a direct consequence of recent and current housing policy, not an accidental by-product.

The Child Poverty Action Group stated recently here

‘Trust for London has made it clear that the cost of housing is the main factor explaining London’s higher poverty rates compared with other parts of the country. London’s housing costs are soaring and more and more children across the capital are becoming homeless as too many of London’s families (both in and out of work) do not have access to affordable, secure, good quality housing. More people in poverty live in the private rented sector than any other housing tenure, and the number of children living in poverty in private rented accommodation has tripled in the last decade.’

I can’t read this as anything but the failure of recent and current housing policy.

So from the success of the social housing of the post-war period, to the failure of contemporary policies to house the population and address inequality, what is the relationship of the London Vernacular to these current housing policies and practices?

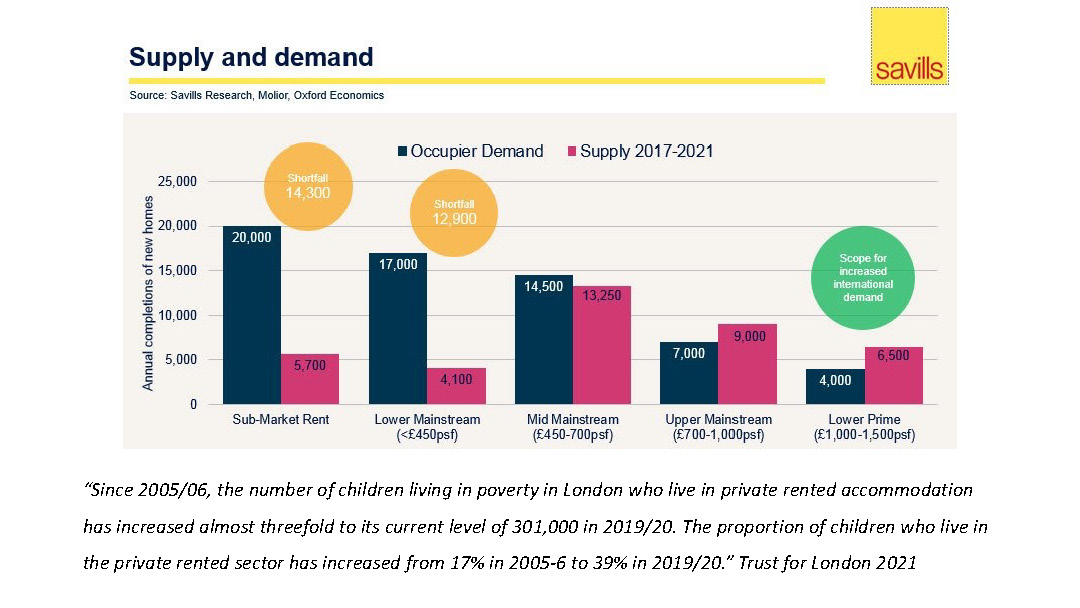

The images below are extracts from Savills’ report to Cabinet in 2016 called Completing London’s Streets. The report explores how the demolition and regeneration of London’s housing estates with the London Vernacular could increase the supply of homes and address what they see as design flaws. I believe it represents one of the clearest illustrations of the way in which the London Vernacular is being used to argue for the demolition of London’s social housing estates – an example plan we see bottom left.

In this report Savills’ explicitly proposes the demolition of London’s estates on aesthetic and formal grounds, on the primary premise that it could increase housing density, land value and house prices.

‘This will not only unlock the delivery of more and higher quality, new and regenerated residential neighbourhoods, but also create a valuable and robust asset with superior value growth’

And on the right alongside an interesting list of assumptions and exclusions:

‘Complete streets is a successful reintegration of the site into the surrounding urban fabric which can achieve values equal to those of the neightbouring period homes.’

While the environmental, social and financial consequences of demolition on existing communities are ignored.

The rise of the London Vernacular really took off within housing policy with Mayor Boris Johnson’s London housing guide in 2009-10, and over the following 12 or so years there have been a number of architectural manifestos on the London Vernacular since then, all of which focus primarily on:

- Materiality – being primarily clad in brick

- looking like a Victorian or Georgian terrace

- accommodating semi-private courtyards

- having a unique street entrance

- being tenure blind

In trying to find aspects of the London vernacular other than those that drive solely towards an increase in house prices, in ‘A New London Housing Vernacular’, a publication by Urban Design London and Design for Homes in 2012, they argue that ‘tenure blindness’ contributes to the homes being ‘fundamentally democratic’. Is this the extent of the political or social ambition of the London Vernacular: the right to look like you own your own home?

These design codes on their own are all very well, but like most things, what is most important is that which is left out of this discussion:

- Where are these homes going to be built?

- Who or what is funding their construction? And who will profit from it?

- How much will the new homes cost to rent or buy?

- What is the environmental, social and economic consequences of their construction?

- And how many additional homes for sub-market, social or council rent are being built – the most in demand housing type.

Following the conservative/liberal coalition in 2010, the conservative think tank Policy Exchange published ‘Making Housing Affordable’ a new vision for housing policy’. A document which is based largely around arguing for the replacement of social housing with home ownership and a range of so-called affordable housing tenures. This was followed up in 2013 with a report called Create Streets – a key inspiration for the Savills’ document – which was a collaboration of Nicholas Boys-smith with Alex Morton of Policy Exchange. One of Morton’s other reports is called ‘Ending Expensive Social Tenancies’, so its clear to see that the aims of these policies are explicitly towards ending social housing.

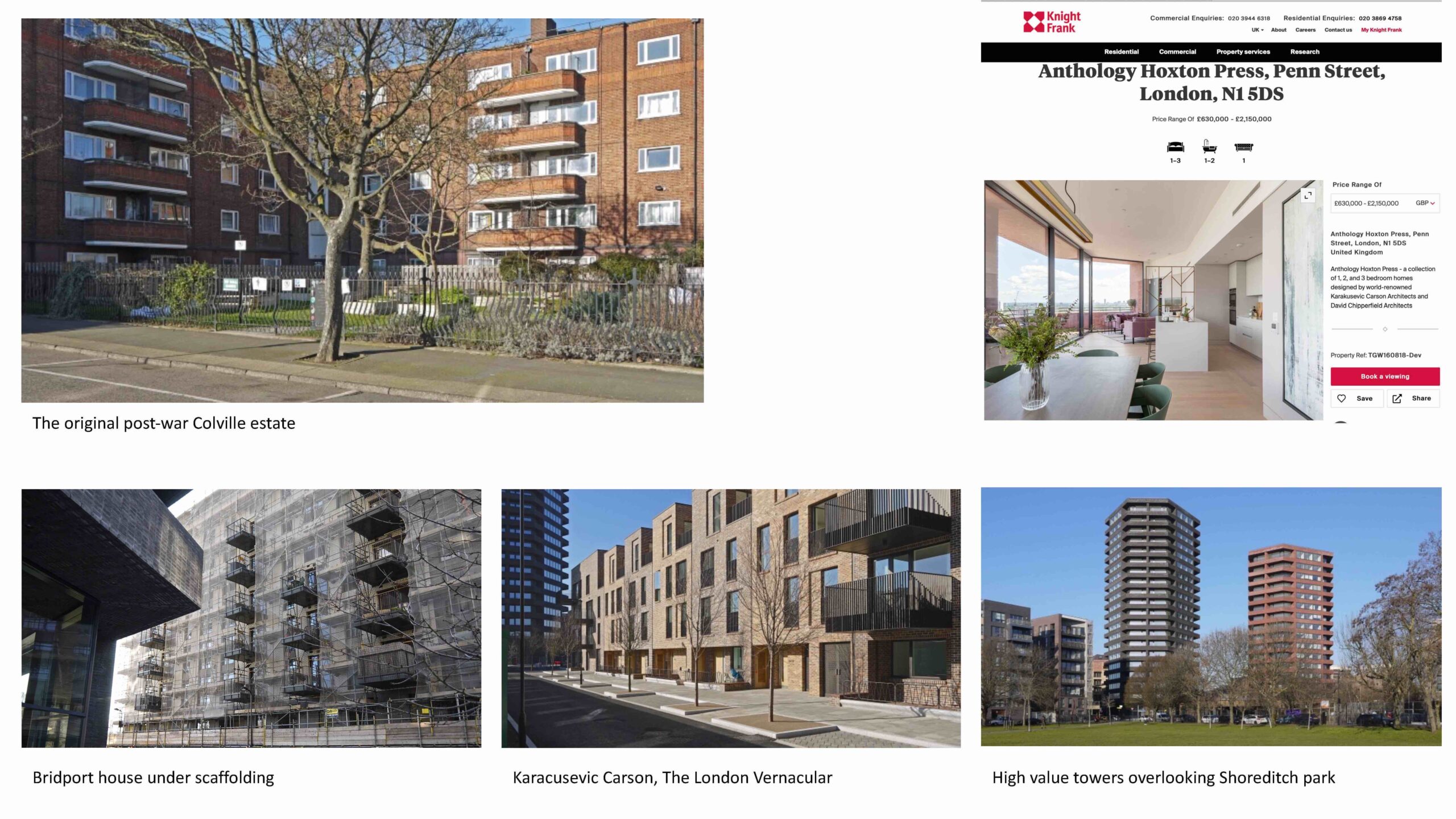

The Colville estate in Hackney by Karakusevic Carson Architects (below) is a very good example of a typical London Vernacular development, given that the vast majority of London Vernacular homes are being built on the ruins of demolished inner city council estates.

The existing post-war estate consisted of 438 homes (seen top left) of which 338 were homes for social rent. As a result of the estate regeneration scheme, these were replaced with 925 new dwellings of which 476 were for market sale, 111 intermediate (meaning shared ownership or shared equity) and 338 for social rent, gaining precisely 0 additional homes for the housing tenure most in demand in London.

As a result of the scheme, the 85 leaseholders and 7 freeholders lost their properties. The sums offered in compensation – for example the £230,000 offered for a 2 bed flat – will only cover around 25% of the £715,000 required for a shared ownership property. Homes in the new development are currently on sale for up to £2.15 million.

If there was one tenure type to epitomise current housing policy and the London Vernacular if would be shared ownership. Mirroring the London Vernacular’s desire for tenure blindness – shared ownership provides the illusion of ownership but is in fact an extremely expensive and insecure tenancy agreement with none of the security of ownership and all the costs of renting until you staircase to 100%.

The purpose of the regeneration of the Colville estate was not to provide additional homes for social rent, of which it provided none, but to free up and privatise the valuable inner London land next to the park and canal for high value market housing, increasing the land value not only of the estate but also of the surrounding area.

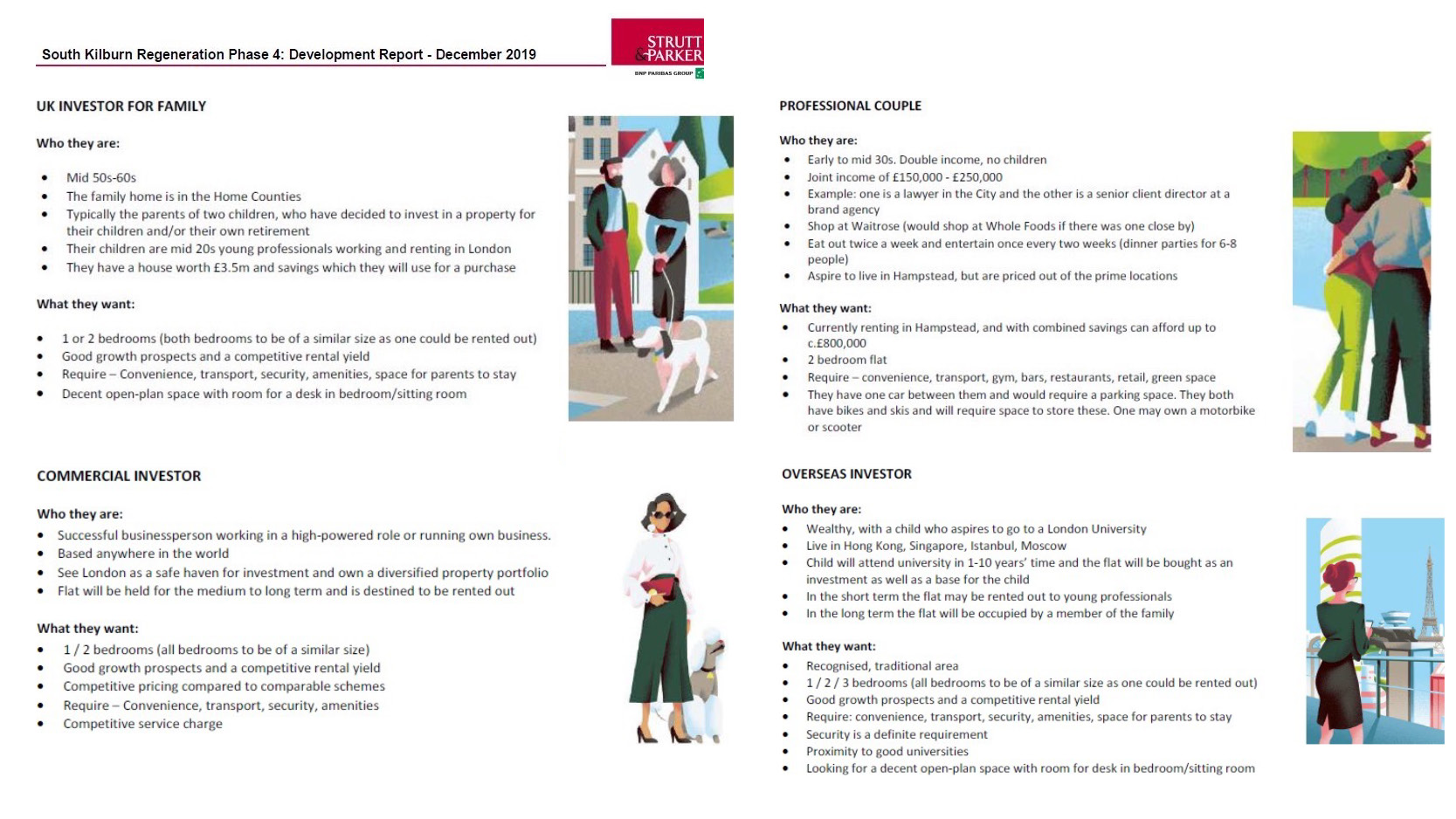

While working on our most recent project,Saving St. Raphael’s estate in Brent, we came across this marketing literature for the adjacent South Kilburn estate, which is currently around mid-way through a 15 year phased estate regeneration. South Kilburn is hailed as an ‘exemplar’ of the London vernacular across London but specifically to its neighbour St. Raphael’s where we were working with residents on an alternative to the demolition of their estate by Brent Council. Here we can see some of the targeted investors who are the subject of this marketing exercise by Strutt and Parker.

Example at top left is the UK investors. They live in the home counties in a house worth around £3.5million but are looking to invest in property either for their own retirement or as an investment for their children. Next we can see the commercial investor looking for a long term rental. Then a professional couple with a joint income of between £150-250,000 currently renting in Hampstead. And finally an oversees investor looking for an investment for their child but in the meantime renting the flat out to young professionals. These properties are designed as investment vehicles for private rental, not as owner occupied homes. They privatise council land, and convert what was council housing into the scam that is shared ownership, and private rented housing, which is – as I showed – the worst tenure for child poverty.

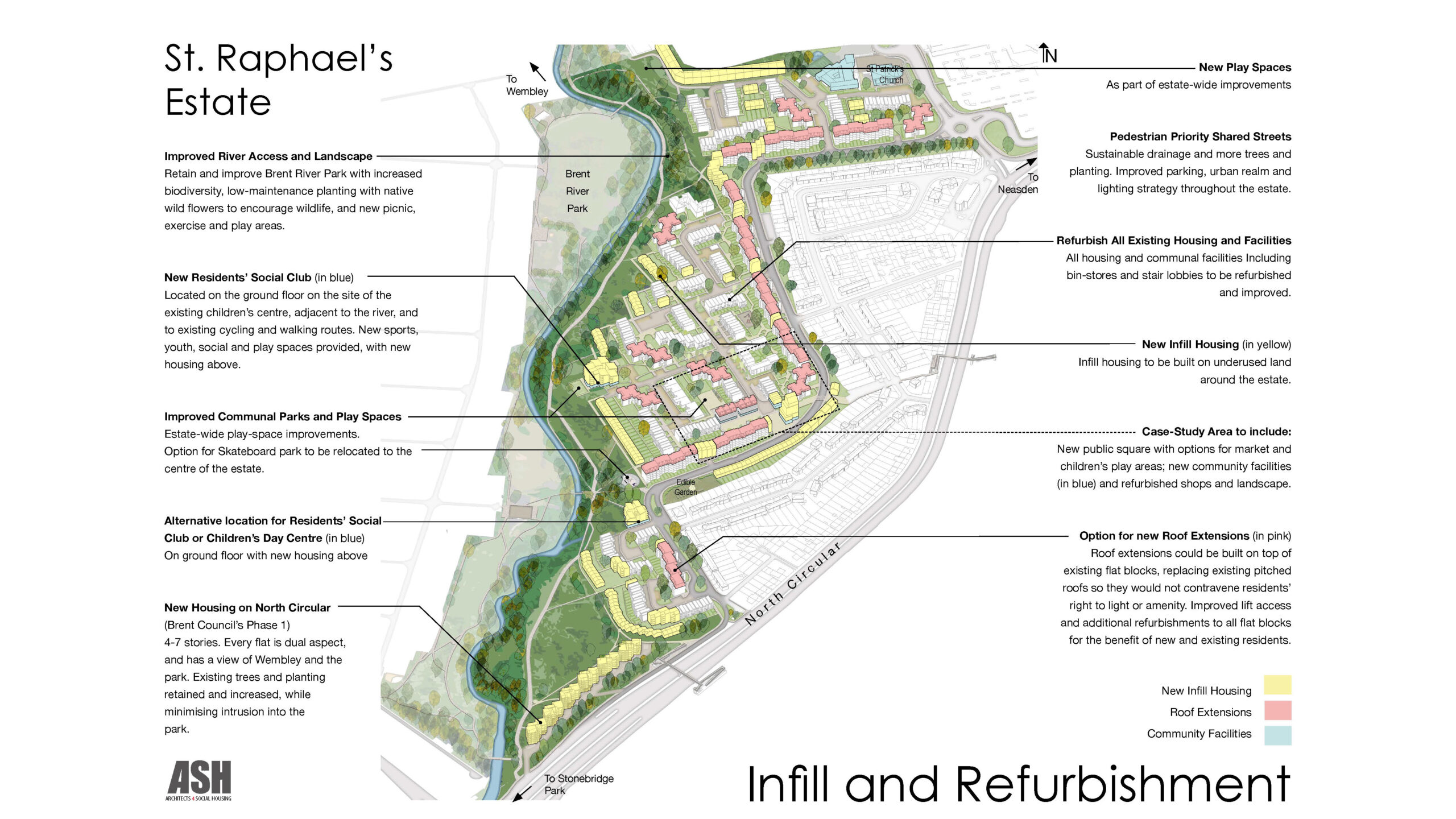

Architects for Social Housing has spent the last 7 years demonstrating that infill and refurbishment is the most socially beneficial, environmentally sustainable and economically viable solution to London’s housing needs, rather than the demolition of London’s social housing and its replacement with investment opportunities.

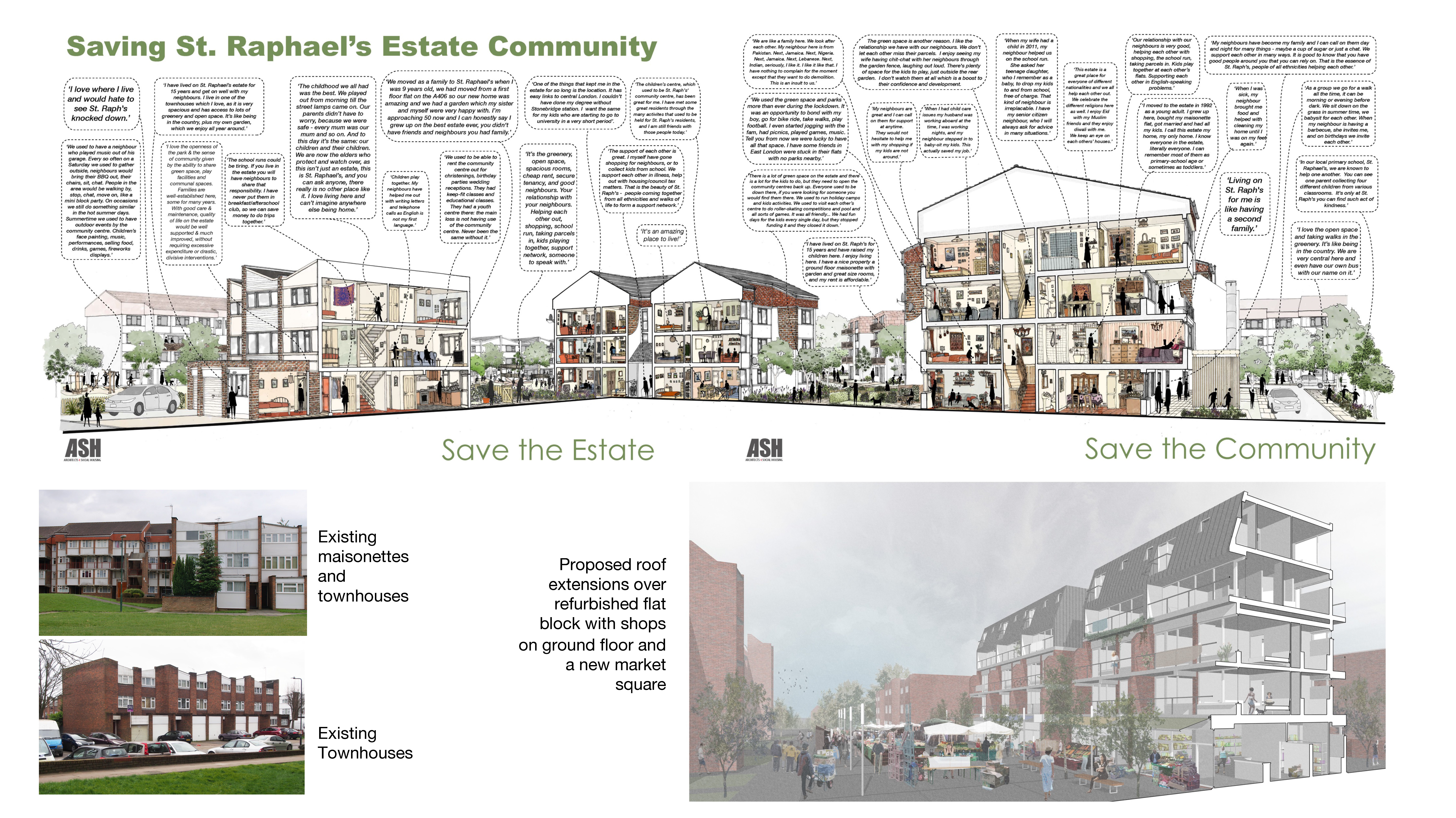

In 2019 ASH was approached by residents of St. Raphael’s estate in Brent to help save their homes from demolition and its replacement with an estate designed in the London vernacular style by Karakusevic Carson. Our subsequent book ‘Saving St. Raphael’s estate: the Alternative to Demolition’ was published in 2022, and includes this image (below top) which contained comments made by residents of the estate stating the reasons they love their homes.

Built in the 1960s to 1970s, around half of the 760 homes on the existing estate are well-made brick-clad (one could argue – brutalist) maisonetttes and flats, and the rest a range of single family townhouses as you can see in these images bottom left.

Working with the existing residents, Architects for Social Housing came up with proposals for infill and refurbishment of all the existing homes, and improvements to the landscape and community facilities. Bottom right you can see an example of the roof extensions ASH proposed on top of an existing block of flats with refurbished shops on the ground floor, as well as proposals for a new market square in the centre of the estate.

ASH’s proposals nearly double the housing capacity on the estate from 760 to 1,368 homes. Of these 845 would be for social rent, an increase of 304 social rented homes. This significant increase in the number of socially rented homes was only possible because our scheme did not have to accommodate the vast expense involved in demolishing and rebuilding perfectly good homes. ASH’s full scheme was costed at £192 million. This was considerably less than half the estimated £537 million for Karakusevic Carsen’s full demolition and redevelopment scheme. Our report also demonstrated that the KCA scheme was in fact unable to provide even enough social rented homes to rehouse the council tenants whose homes would be demolished – let alone any additional ones – and was therefore financially and socially unviable. Brent council subsequently admitted that the KCA scheme was indeed not financially viable, and took the demolition option off the table. They are now pursuing an infill option similar to the one we proposed here (the key difference being they are not proposing to refurbish the existing homes.)

In additional to the social and economic consequences of demolition and redevelopment, any scheme that claims to be any kind of solution must engage with its environmental contexts. As part of the report, we commissioned an environmental engineer who calculated that to demolish and rebuild the existing homes (in the London Vernacular style to KCA’s design) would produce approximately 100,000 tonnes of CO2. That is 400% greater than that produced with ASH’s infill and refurbishment scheme. In addition, they also estimated that, even if the new homes were built to the best Passivhaus standards, the comparative energy and carbon theoretically ‘saved’ in use over the 60-year lifespan of the new buildings would not offset that produced as a result of the demolition and redevelopment of the existing estate.

To Conclude:

The New London Vernacular, rather than producing ‘resiliant design’ and ‘acceptible typologies’ is actually making the housing situation in London worse. By making aesthetic and formal arguments for the demolition of London’s existing housing estates, current housing policy using the new London Vernacular is resulting in the loss of social housing, privatising what was public land, driving up house prices, and pushing residents into shared ownership scams or into the private rental market.

As our book report Saving St. Raphael’s Estate demonstrates, we argue that the most socially beneficial, environmentally sustainable and economically viable solution to addressing London’s housing needs is not to demolish existing post-war housing estates (brutalist or not), but to retain and improve the existing built environment, sensitively infill to increase density, make improvements to the existing landscape and community facilities and to retrofit the existing housing to the latest Enerphit standards.

Any supposed architectural solution that isolates its aesthetics and deliberately ignores or distracts from its social, economic and environmental contexts and consequences is part of the problem, not the solution.

Architecture, after all, is always political.

Geraldine Dening, 2023