The Drive Co-operative

Walthamstow, London

Over the past few years, Architects for Social Housing has increasingly explored alternative ways of funding and building social housing to the current mainstream of local authority and housing association, which is signally failing both existing residents and those in housing need.

In accordance with the neo-liberalisation of housing provision in the UK, housing associations currently only provide 14 per cent of their housing for social rent; while the ongoing estate demolition programme, embraced by every council in London and increasingly by councils across England, means that local authorities are demolishing far more social housing than they are providing, replacing it with market-sale, market-rent, shared-ownership and other so-called ‘affordable’ housing products.

In addition to this demolition, sale and conversion of social housing by these nominal ‘Registered Providers’, in June 2017 the Grenfell Tower fire revealed the importance of the relationship between residents of social housing and their landlord, casting a deadly light on the absence of agency residents have to engage with and influence the maintenance and safety of their homes. The structure of the Kensington and Chelsea Tenants Management Organisation was exposed as catastrophically flawed as a mechanism through which to ensure residents’ needs are listened to and met by landlords and local authorities.

Co-operative housing, by contrast, is managed — and sometimes partially or completely owned — by the residents themselves, and therefore offers potentially interesting solutions to some of the problems of unaccountable landlords, sloppy, withheld or dangerous maintenance, and our rapidly dwindling stock of social housing.

Historically, co-operatives in the UK provide only a small amount of social housing, with 0.6 per cent of all housing in the UK owned co-operatively. But this is not the case in other parts of Europe, where co-operative housing is a much more significant provider of social housing. Norway, for example, has 14 per cent of its housing provided by co-operatives.

The Patmore Estate in south London, which ASH has been working with over the past 3 years, is an interesting example of how the co-operative model could be applied to the management of a large council housing estate, in which residents form the co-operative board and oversee the management of their estate. The Grenfell Tower fire, and the deaths of 72 residents it caused, simply could not have happened under this structure.

In August 2017, during Architects for Social Housing’s residency at the ICA, members of the Drive Housing Co-operative attended some of the events we organised. ASH was subsequently approached by the co-operative to undertake a feasibility study for increasing the size of their existing housing. Our subsequent work with the Drive, which concluded in February 2019, was an opportunity for us to explore how the co-operative model might provide social housing which — unlike both council and housing associations — is not only managed by its residents but also designed to meet their housing needs.

Once ASH was appointed for the feasibility study, we started by holding a number of workshops to interrogate the brief with the client, which in this case was the co-operative residents. This helped us to understand the motivations for the development of the Drive, so that we could make the most informed proposals and recommendations.

The briefing process is a crucial element to get right, because it sets up the criteria, principles and ambitions for the whole project. The brief needed to reflect both the needs of individual members as well as the broader ambitions of the co-operative, and the design proposals needed to translate these co-operative values and ways of living into architecture — spatially, materially and formally.

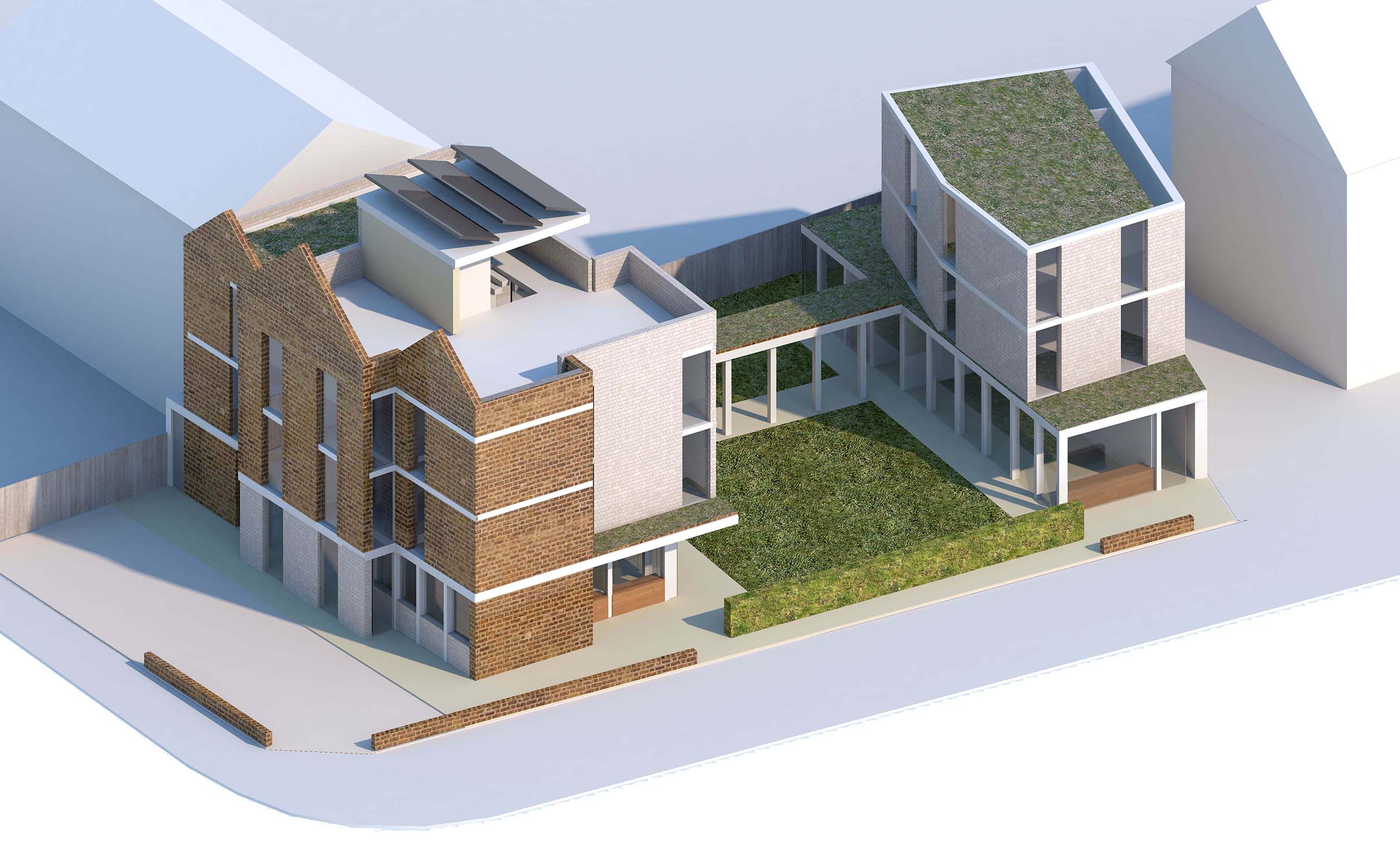

The formal and material properties of the existing house were important in terms of the memories they held for the residents, and on an urban level as they formed a part of a historic street pattern.

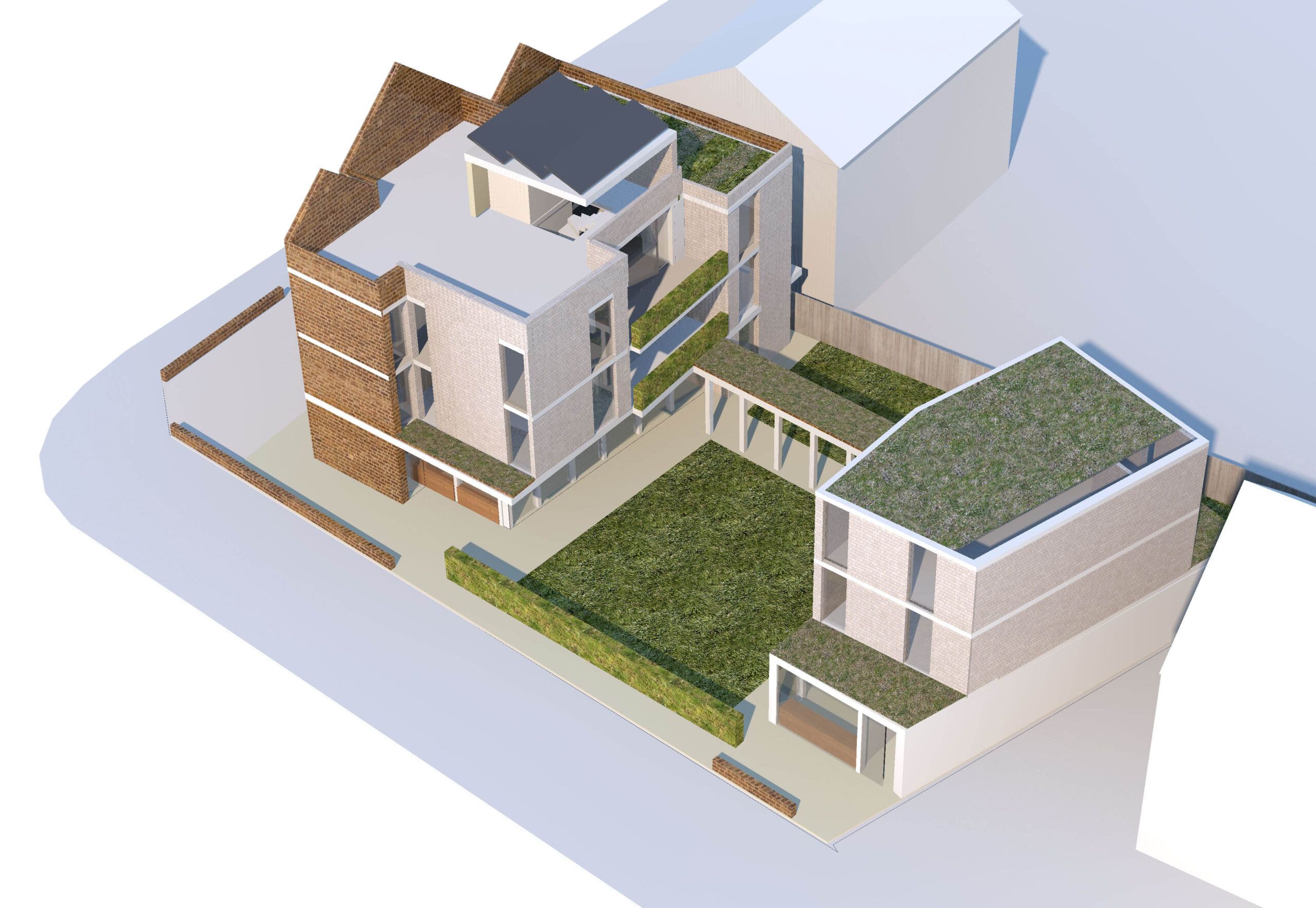

In the new-build option we therefore explored ways we could retain some of these qualities formally through the use of pitched roofs, the shifting relationship of the facade to the street, and in the proportions of fenestration; and materially through the reuse of the existing bricks and other details.

The fundamental questions around which the brief revolved were:

- Whether to refurbish or demolish the existing building, and the various consequences of both options;

- How to achieve the most financially, socially and environmentally ‘sustainable’ development;

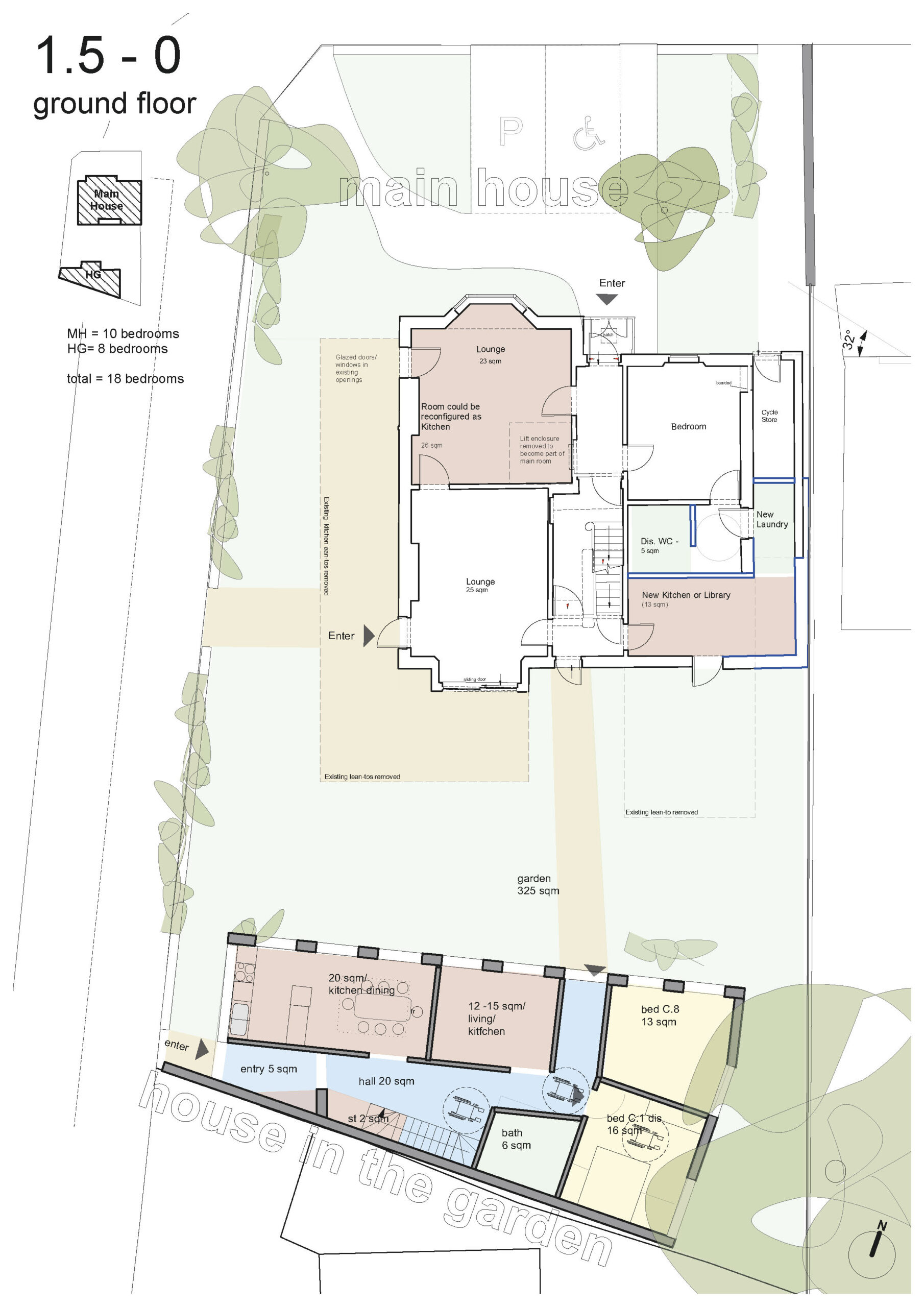

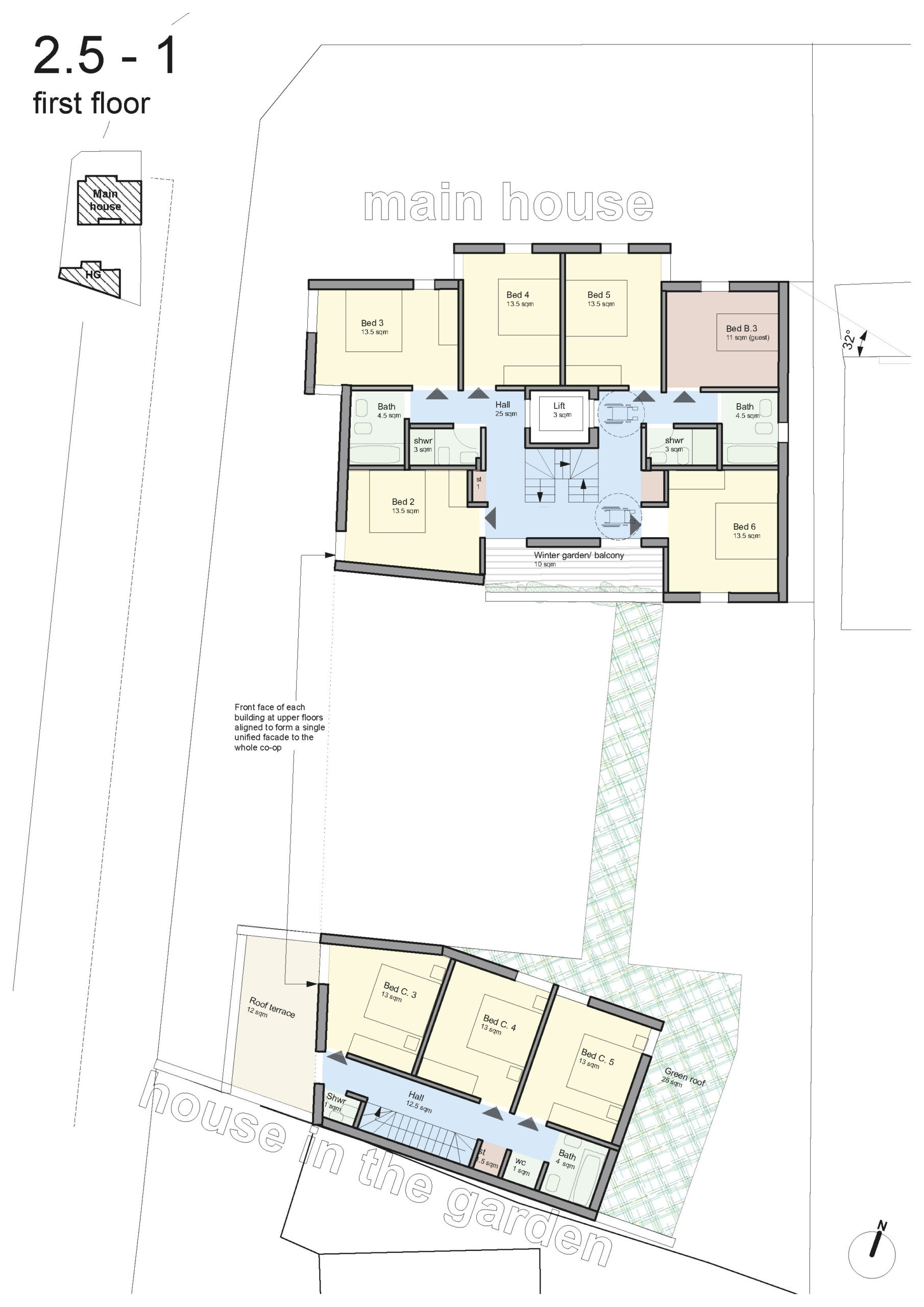

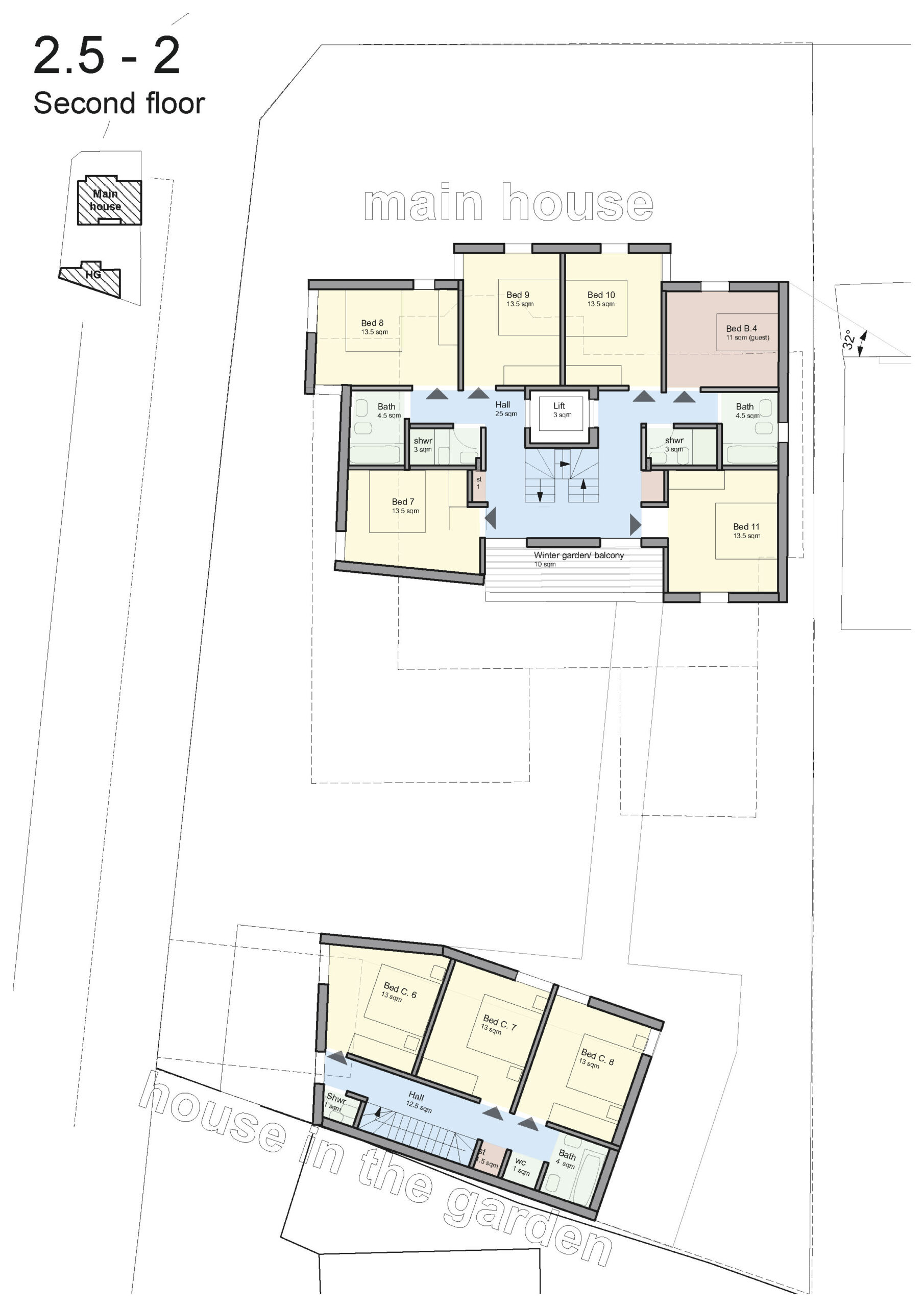

- How the existing household of 10 people – an intimate co-housing unit – could double in size to provide additional housing at low cost rents and yet retain the key and particular qualities of co-operative living that the Drive embodies;

More broadly this enabled us to explore how we could translate these co-operative values and ways of living into architecture — spatially, materially and formally.

Some of the key architectural moves we used to achieve this – which emerged out of extended workshops and conversations with residents were:

- The importance of the circulation and shared spaces to the quality of collective experience;

- The provision of shared outdoor balconies/ winter gardens on each floor;

Something we brought to the project was the idea of flexibility and change of use over time. This lead to early thoughts around key structural decisions which would enable layout changes over time including different configurations for the private quarters as well as the more public, or semi public areas.

We also designed an option in which the layout could be entirely reconfigured to accommodate private flats with no major structural work

The new courtyard garden is designed as the centre of the new co-operative around which life in both the new ‘house in the garden’ and the main house revolves: all the main shared spaces overlook this space, and it is orientated to make the most of the afternoon sun.